|

_________________________________________________

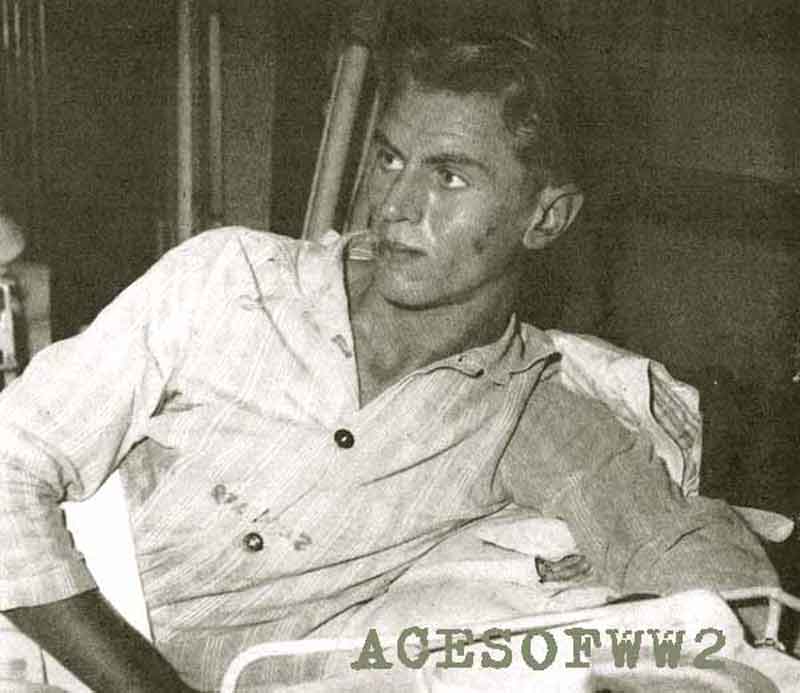

The Nazi-killing odyssey of "Screwball" Beurling,

top ace of Britain's RAF, turned down in 1940 by the Canadian Air Force

because he hadn't cut his cultural teeth.

WHEN George Beurling walked into the Royal Canadian Air Force recruiting

center in Montreal, about the time France fell, and told them he wanted

to be a Spitfire pilot, the officer-in-charge brushed the youngster off

with a laconic "Sorry, son, but you haven't had enough schooling

to fly with the RCAF. Come back when you graduate." When Beurling

asked if they'd like to see the private pilot's license he had earned

by scratching every dime he could find for flying lessons, the answer

was simply "Sorry." Whereupon the seventeen-year-old went away

from there, fit to cry, but still convinced he had been born to «hoot

down Germans.

When Pilot Officer George Beurling, of Britain's Royal Air Force, not

Canada's, came back to Montreal on leave from Malta two and a half years

later as the third-ranking combat pilot of the British Empire and first

in the immediate records, the higher learning was still missing, but his

point had been proved. Instead of doctorates and magna cum laude credentials,

the kid from the wrong side of the tracks brought home a tally of twenty-nine

enemy planes shot down, all but the first pair in less than four months

of action over Malta, plus a number of "probables" and "enemy

aircraft damaged," plus four decorations for outstanding bravery

and a commission won in battle. The faces of the Canadian recruiting officers

were noticeably red.

What happened to Beurling during the intervening months is spun from the

same stuff with which the lamented Horatio Alger, Jr., used to inspire

Young America to great deeds a couple of generations ago. The RAF has

a motto for it in the Latin tag which appears on the insignia of the force,

Per Ardua ad Astra, a free translation of which might read "To the

stars, the hard way." That was Beurling's route.

The day the Canadian Air Force turned him down for lack of the three R's,

the boy went home and did some heavy solo thinking. Home was, and still

is, the upper flat of a weatherworn frame cottage in Verdun, a working-class

suburb of Montreal.

He shut the bedroom door and pondered a life-ruined by red tape before

its eighteenth birthday. Gone were all the dimes and quarters and dollars

he had scrimped to buy flying time from Ted Hogan and'' Fizzy " Champagne,

the prewar bush pilots who had been his civilian instructors. That's what

comes of preferring engines to high schools! But you can't kill an obsession

just by saying "No" to the party-obsessed. By the time George

rolled into bed his mind was made up. Somehow he would make his way to

England and see if the hard-pressed British could use a guy with a private

license and a yen to fly fighters. Within a few days he was at sea, working

his way across on a merchantman in convoy.

In England, Beurling told a recruiting officer his story. The officer

said, "Splendid. But have you your parents' permission to join up?

After all, you're a minor, old boy!" George shipped for the return

trip to Canada, to get a letter from his folks.

The Nazis scored a hit on his ship, but it stayed afloat and limped into

an anonymous east-coast port, whence the young man hotfooted it to Montreal

and the little house at 315 Rielle Avenue, Verdun. With money earned during

the two-way Atlantic passage, he hired a car and took his mother riding

in the country. The outing was what mom calls a "treat," since

the family doesn't own a car, though Beurling pere paints them with a

spray gun in the body plant where he works. Mrs. Beurling's passion for

motoring made the boy's task easy. Once the papers were signed, the lad

waited just long enough to pick up his laundry and kiss the folks good-by

before returning to Britain on a munitions ship. This time the recruiting

officer said "Yes," and Beurling was in the RAF.

The kids who fly the Spitfires are good pilots. They have to be good to

survive. And once in a while one turns up who is superb. Such young men

combine flying skill with marksmanship in such perfect co-ordination that

every movement they execute while the undercart is up is performed as

if flying and shooting were one and the same thing. It is that strange

magic called timing, and either you have it or you haven't. Beurling has

it, plus the approach of a scientific perfectionist to his trade. His

squadron leader in Malta calls him “the perfect mathematician of

the air," going on from there to discuss the precision of the deflection-shooting

by means of which the young man bagged most of his kill. That means timing

your burst to arrive at a given point at the precise moment when the enemy

reaches it, and it is a matter of split-second reckoning relating to two

planes, yours and the victim's, which will be miles apart a minute later

if you miss.

"People keep asking me what my system is," Beurling says. "It's

a matter of training your eyes to focus swiftly on any small object that's

out there. The trickiest part of this is deflection shooting, or shooting

across the beam of an enemy aircraft traveling 300 miles an hour or better.

It means you fire well ahead of it, if your bullets aren't going to pass

hopelessly behind. I've never stopped practicing this."

It was 1942 by the time the young transatlantic wayfarer had shucked off

all the red tape and worked his way up to sergeant pilot's rank and was

posted for combat duty to an operations squadron in Britain. Things were

pretty dull in Western Europe. Now and then he picked up a dogfight and

once was caught flat-footed under a cloud bank by five Focke-Wulfs while

alone on a sweep over Occupied France.

Before they could get him, Beurling had let down the wheels and the wing

flaps and yanked the slowed-up Spit into a tight inside loop. By the time

the visitors spotted him again he was a speck in the distance, heading

for home. That, he says, is the only time they ever caught him off his

base.

Over France he picked up his first two scores, but he was still just another

young pilot called George when he went to the orderly room and asked his

commanding officer for a transfer to Malta, where things were happening.

He went there in June.

The going was hot in Malta last summer. The Germans and Italians—

Beurling insists the latter are better fliers than the Nazis—were

pasting the island day in and out and attacking British convoys headed

for Gibraltar or Egypt. Enemy convoys were thrusting across the Mediterranean

to reinforce and supply the Afrika Korps, and their aircraft were running

a day-and-night shuttle service over the main line. Allied fliers were

banging Rommel's rear and going to work on Axis shipping, in addition

to providing their own with an umbrella.

Beurling's mates say he would make six, seven and sometimes eight operational

flights a day. When he wasn't flying he was either practicing gunnery

tricks or boning up new ideas to be tested in tomorrow's battles. The

citation for his Distinguished Flying Cross called him "an exceptional

pilot who continues to be the inspiration of all who come in contact with

him." But his fellow pilots christened him "Screwball."

In the first days at Malta he was undisciplined and cocky. You can't peel

out of formation and go hunting on your own whenever the whim occurs and

make friends. But it didn't take long to convince Beurling that he couldn't

fight a one-man war. Once he had accepted that and settled into the groove

he began to go places. A lot of credit belongs to his RAF bosses. They

might easily have destroyed his spirit during the deflation process, but

they left it intact.

Blunt speech, easily mistaken for freshness in a youngster, was George's

hallmark—and still is. There was, for example, the incident which

the literati of the RAF are wont to mention as The Case of the Refused

Commission, whenever the Beurling saga is being examined, which is daily

in most fighter messes. It happened before George went to Malta. His commanding

officer, a paternal gentleman, had been thinking how nice it would be

if a youngster of promise were invited to eat at the officers' mess. Any

other sergeant pilot on the station would have jumped at the chance. Not

Beurling.

"Look," he said, "I'm not the sort of guy who should be

an officer. I'm better like this."

No Desk Flier

"But," countered the wing commander, "don’t you want

to get ahead? Don't you want to be in command of a station someday?"

"Wha-a-a-at!" cried Beurling, horrified. "Spend all my

time flying a desk? No, sir, not me!"

He didn't get the commission—not until the kinks had been ironed

out. Even then he let it be known that he didn't particularly want it.

By the time all the medals had been distributed and the pilot officer's

suit acquired, Beurling's brashness was curbed, but the flair for forthright

speech remained. Only he now applies it to the enemy and to the day's

work.

A strange mixture, this young flier. You think of a cold-blooded killer;

then he says that, if he had the courage to stick it out until he made

the grade, the credit belongs to his parents for their encouragement and

the kind of home-life background they had given him. You think of a hard-spoken

kid; then he wilts with emotion when the Prime Minister of Canada shakes

his hand. Many things have happened to this externally case-hardened youngster

during the past two years, and. most of them happened the hard way.

On one point his seniors were unanimous while they were hammering discipline

into him: the boy was the best combat pilot to turn up since Paddy Finucane.

Beurling was sending Huns into the sea in flames, in clouds of smoke,

in bits and pieces. He shot them down singly and he shot them in bunches.

On July twelfth he knocked off three Italian Macchi 202's. He had other

triple-killing days and, on July twenty-seventh, he hit the jack pot by

shooting down two Messerschmitt 109's and two Macchis and damaging two

other 109's.

Decorations began to come his way in midsummer, while he was still Sergeant

Beurling. The Distinguished Flying Medal came when he had shot down his

eleventh enemy plane and his ninth at Malta. The bar to his DFM was awarded

a few weeks later. Meanwhile the ex-problem child had been commissioned

pilot officer, despite his restated aversion to "spit-and-polish."

After moving his kit across to the officers' quarters he took to the air

and went Hun hunting, just to prove to himself that his new status didn't

mean a thing. On October tenth he was awarded the Distinguished Flying

Cross for "destroying two enemy fighters and probably a third, in

a matter of seconds."

On October twenty-third he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order,

second only to the Victoria Cross, for his exploits nine days earlier

when, in addition to destroying three enemy aircraft, he saved his flight

commander from certain death by removing a Hun from the gentleman's tail

by the accepted Beurling method, a quick burst of gunfire.

That day he destroyed two 109's and a Junkers 88 before his controls and

a piece of his left heel were shot away. For the first time "Screwball"

took to the silk. When a crash-boat crew fished him out of the Mediterranean,

he told them the parachute ride had been swell fun.

The medicos at Malta dried him out and encased his wounded heel in plaster

and he was furloughed. At Gibraltar he sat around moodily for several

days, waiting for a transport plane to carry him to England. But the strange,

charmed odyssey of the boy who refused to be kept out of the war was not

ended. As the huge Liberator took off from the Rock it tripped on a hilltop

and catapulted into the sea, killing sixteen passengers and crew members

and seriously injuring eleven. Young Mr. Beurling came ashore with superficial

bruises! In Britain he rested briefly in hospital, then caught a Canada-bound

ferry plane.

The kid wilted under the withering fire of the home-front welcome.

Mom had been saving her sugar coupons against this day and piling her

pantry shelves high with pies and cakes. Pop was thinking seriously of

taking a day off from the body factory. Ten-year-old Dick was counting

the hours to the time when he would sit across the kitchen table from

his brother and George would tell him how it was done. Five-year-old Dave

simply wanted to look at the hero, and sis and her husband figured to

drop around for a talk. Maybe pop would read a chapter from the Bible,

and the reunited family would thank God together for George's safe return.

In all of which the Beurlings counted without the Canadian government,

Montreal's million residents and the press liaison officers of the Air

Force.

Life Becomes Too Strenuous

First the family was invited to be at the flying field

at a given hour in the evening. They went in their Sunday best. Pretty

soon a ferry-command officer came along and said "Any minute now,"

and a big bomber slid in along the runway. Flashlights popped. The bomber

door opened and Pilot Officer Beurling stepped out. Mother, father, sister

and brothers all embraced the returning hero. Then the shooting started.

Lock, stock and barrel the Beurlings were bundled into the big ship, mom's

new hat slightly awry and her voice complaining that her feet ached. With

that the door slammed shut and the ship taxied out for the take-off. Forty

minutes later the Beurlings landed at Ottawa, to be whisked to a hotel

suite and whisked right out again to the Parliament Buildings to meet

Prime Minister King. Everybody said how proud they were, the Prime Minister

to meet George, and all the Beurlings to meet the P. M. Then they were

whisked back to the hotel, where George went to sleep before they could

get him out of his uniform.

During successive days the hero of Malta was rushed from reception to

reception, from luncheon to dinner party, from broadcast to broadcast,

while mom sat at home wondering when George would be coming home to get

some sleep and go to work on the pies.

Finally he collapsed in a broadcasting studio, shortly before he was due

on the air for an interview. Officialdom, alarmed, sent for the sawbones,

who prescribed complete rest.

To all these goings-on Pilot Officer Beurling had one major contribution

to make. That was in the auditorium, down home in Verdun, the night of

the big welcome. Girl Guides had just come to the dais to present him

with twenty-nine red roses, one for every notch in the handle of his gun.

Beurling took the roses and handed them to mom. When the applause died

he thanked his townsfolk nervously; then, clearing his throat and visibly

dying a thousand deaths, he said: "This is no place for me! I'm a

fighter pilot!"

That was the old "Screwball" Beurling of Malta, worn down to

his uppers, but telling the world that the odyssey isn't finished yet!

_________________________________________________

--- Beurling ---

--- Canadian Aces ---

_________________________________________________

On these pages I use Hugh Halliday's extensive research which includes info from numerous sources; newspaper articles via the Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation (CMCC); the Google News Archives; the London Gazette Archives and other sources both published and private.

|

Some content on this site is probably the property of acesofww2.com unless otherwise noted.

![]()