|

_________________________________________________

Not long ago George Beurling, Canada’s best fighter

pilot in the last war, sat inside a Montreal hotel room and brushed aside

with a few words his unhappy experiences as a civilian so he could see

more clearly and live again the best years of his life.

When Bearing, who is now 26, talks of air combat, his tanned boyish face

glows with happy recollection and present excitement. For he remembers

it all clearly. He remembers every detail of every fight in the air—the

date, the hour, the altitude, the direction he was flying and best of

all the deflection he gave the shots that batted the enemy down.

His official score was 31 destroyed, highest of any Canadian.

“I would give 10 years of my life to live over those six months

I had in Malta in 1942. The food was lousy and we were bombed all the

time. My weight dropped from 177 to 126. But the flying weather was good

and every time you went flying the sky was full of Germans to fight,”

Beurling said. In those desperate days on the George Cross island, he

shot down 28 aircraft and won every air decoration for fighting except

the Victoria Cross.

Heartless young Beurling, who has found the years of pence dull and disappointing,

may soon get his wish to see life again through a gun sight. He said in

Montreal that he had been approached by warring factions in the Near East

to fly as a combat fighter pilot.

Beurling refused to be quoted on the reply he had made to these advances.

But he added: “I would be glad to get back into combat. It’s

the only thing I can do well; it's the only thing I ever did I really

liked.”

When asked about the restrictions already imposed by the U. S. State Department

to keep citizens from going to Palestine to fight, and possibly to be

invoked by Ottawa against Canadians, Beurling said: "I've been through

all this before. I was all set to go to China in 1944 to fight for the

Nationalists. The pay was to be $1,500 a month in U.S. funds on the barrelhead.

Good dough. But Ottawa stopped me from going. I also got an offer from

the Chinese Communists not long ago."

Since his discharge, Beurling has flown commercially for other men who

had their own companies, flying fishing and hunting parties into the bush,

hauling freight and passengers. In between jobs like these he has sold

life insurance (he couldn't stand it), hunted deer in Cape Breton with

bow and arrow, taken passengers up for 15 minute flips at fair grounds,

fished under water wearing goggles and armed with a spear, skied and done

lots of fishing on his own.

Can't Settle Down

OH, IT'S been all right. I'm not kicking. I've made out all right for

money. I used to get $500 for 15 minutes stunting down in the States.

One day I made $690 carrying passengers in a Norseman down in the Eastern

Townships. I've worked for a while and then gone fishing for a while.

It's been all right but I've never been able to settle down." said

Beurling.

The only aircraft Beurling now has is a Tiger Moth, specially stressed

for aerobatics. He holds a commercial pilot's license with the Department

of Transport and has logged about 4,000 hours, including his combat

time.

He often thought of starting his own little charter company and has

owned his own planes at various times. He had the backing, too. He says

Harry Ship of Montreal and Ernie Buckerfield, the West Coast grainman,

had both repeatedly offered to back him in any project he wanted to

undertake. But it has never worked out that way and he has never settled

down.

"And I'm glad," Beurling now says. "It leaves me clear

and without any strings to go back to the only thing I really love—combat

flying. I've never really wanted to be a commercial pilot or an airline

pilot. I know that now! I'm a fighter pilot."

Beurling has few of the usual patriotic feelings of a man for his country.

He thinks he did a job for Canada during the war, no more than he should

have, though, and somehow Canada has failed to do right by him. He doesn't

know exactly where the shortcoming has been and he doesn't blame anyone

in particular.

But he has never felt any great sympathy or understanding for other

young Canadians. The reason for this is he feels, that he has never

been interested in anything but flying. When his high-school contemporaries

were starting to go out with girls and swaying around juke boxes listening

to Ella Fitzgerald's reading of a "A Tisket, A Tasket" and

Connie Boswell's swing revival of "Martha" he was learning

a roll off the top and perfecting dead-stick landings.

"There are times when I feel I am more a European than a North

American," he said.

Who Needs a Fighter?

BEURLING ran a hand through his straight blond

hair that has a tendency to slide down from the high-crested pompadour

in which he combs it and waggled a nail file in the other hand to

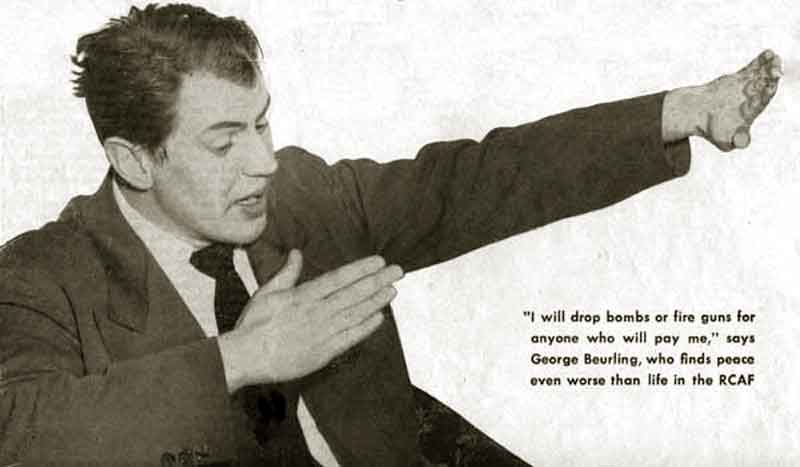

accent his next words; "I know it may sound hard, but I will drop bombs or fire guns from a plane for anyone who will pay me. And I will fly for the one who will pay me the most," he said. How about Russia? "Except Russia," he said. "I don't like the Russians." Beurling was asked if he was interested in the politics of any of his prospective employers. "I'm interested in politics, and I read a lot about them, but only to find out where the next war is going to be and where they will need fighter pilots. Other than that all I ask is 'How much will you pay me?'" he said. What was he going to do with all the money he made as a mercenary, or did he think he would live to spend it? Beurling shrugged his shoulders. |

"I don't like the Russians" |

Beurling doesn’t blame anyone for the way things have failed to work out since he climbed down from his Spitfire. He's not bitter, although it amuses him in an acid way that some of the people who were pelting him with roses and big hellos in 1942 when he came back to Canada on a triumphal bond tour now wonder where they've seen him before.

Beurling is even ready to admit that one of the big reasons for his failure to rehabilitate successfully lies within himself. He knows he is different and that the world is rarely kind to people who are different.

"I'll tell you the difference between me and most of the fellows who were in the Air Force," he said. "Most of us who went into fighters went because it was the softest place to fight. In the Air Force the bombers' crews were the real heroes. They did the dirty, dangerous, heavy work. In the Navy you lived hard and got seasick and in the Army you died in the mud. So we went into the fighter force where every man was captain of his own aircraft and slept in his own bed at night.

Fighting's His Life

"But to most of the boys I knew, being in the Air

Force was just an interlude. They studied deflection shooting, enough

to get by and they had no more curiosity about it. They learned to fly

and now that they're out they are back at their jobs and have no desire

ever to pilot an aircraft again." Beurling said this last with a

rising note of surprise in his voice. The surprise was genuine, for he

cannot imagine anyone not being interested in flying once he has flown.

He cannot imagine a man losing his interest in deflection shooting once

he has lined up the rings on a target in combat.

"Me - I've been flying ever since I was 14. I started flying

near Montreal. Ernst Udet, the German and to me the greatest flier of

all time, taught me aerobatics. I will always fly. And as for shooting,

guns and shooting have always been my hobby. I am always thinking of angles

of fire. Even when I walk down the street I look at the angle at which

telephone wires cross the line of a building. I calculate angles as I

walk along and sometimes stop and go back to check an angle. The way pianists

can enjoy music by hearing a note in their heads, that's the way I am

about angles." He spoke like a man deep in his favorite subject.

Deflection is the angle by which a fighter pilot must aim ahead of his

opponent's speeding plane so that his bullets and the plane end up in

a tie in the sky. To aid ordinary fighter pilots in making these swift

and complicated calculations the Air Force supplied them with a gyro gun

sight which anticipated the angle of the fire for them. Pilots said of

Beurling that he carried his own gun sight in his head, so keen were his

eyes and so swift and faultless was the calculating equipment he had in

his brain. Beurling says he can see three times as far as most people.

"I could do just about as well with a plain ring sight as I could

with that Air Force sight which could never promise more than 15 or 20%

hits," said Beurling. "In fact, I have designed my own sight

which will guarantee 60% hits. I've made a working model of this and checked

it every way I can, short of actual air combat, and I'm sure it's the

best air gun sight in existence."

He was asked what he would do with it. Beurling grinned.

"It's going with me. I need it in my work."

Would he patent it?

"Perhaps," He said. "Just so long as the RCAF doesn't get

it."

His War With the RCAF

Beurling first clashed with the Royal Canadian Air Force

a year before the war when he entered the aerobatic competition at a light

plane air show in Edmonton. Two RCAF fliers also competed and Beurling,

trained by Udet, then a commercial instructor in Portland, Ore., a year

before, won against both of them. Beurling rode the rods to the west coast

and took instruction from the famous flier with money he had saved. As

he stepped forward to receive his prize from a senior RCAF officer, George

remarked with a characteristic candor that often antagonizes people (much

to his surprise), "If that's the best the RCAF can do, it better

get some pilots."

Beurling is convinced that this was the reason the RCAF did not accept

his application in 1939. He went then to England and the RAF.

"I guess I sometimes rub people the wrong way, but I can't stand

sloppy performance no matter where," he said. "I have to mention

it."

Flight commanders, squadron leaders, wing commanders and brass hats have

all been given a wrong rub by Beurling who has often chosen exposed and

public places to make his blunt pronouncements.

"It was that way I got a reputation for being a wild flier,"

said Beurling. "I'm not a crazy flier. If I were I wouldn't be alive

today. I've never scratched an aircraft because of my own error.

We were giving an air show in Malta to raise the morale of the Malts and

two wing commanders chose me to fly with them on this beat up. We flew

down a broad street dropping down below the level of the roofs. The wing

commanders told me to fly down the center straight and level while, they

formated on me. When we got back I didn't think much of this and I told

them so. They asked me what I would have done. I showed them. I flew down

the same street 50 feet off the deck - upside down. That's aerobats,

I said when I got back. And they got sore. I was a sergeant pilot at the

time."

When Beurling first went on operations in England he was posted by the

RAF to a Canadian squadron because he was a Canadian. On one of his first

operational flights he tangled with authority and sowed the seeds of fact

and legend that later blossomed into his reputation.

"The squadron leader was a Canadian and he was permanent force. He's

also dead now so there's no point in mentioning his name. He told me to

fly tail end Charlie in red section, my usual spot. We were in the air

with our tails in the sun by the way, vulnerable to attack, when I called

up and reported Huns. The squadron leader gave me hell and told me to

stop trying to cause trouble in the air and to stop reporting Huns that

weren't there.

"Ten minutes later we were bounced and I got shot. It wasn't bad,

just a sliver of cannon shell that grazed my ribs. But I got a German,

my first, that day. When we got back on the ground I had my turn and bawled

the squadron leader out. I told him we might all have been killed."

Beurling, who was a sergeant at the time, had a feeling that there wasn't

much of a future on the squadron for him, so when a posting came through

for a squadron mate who had put in for Malta and had then got married

and wanted to stay in Britain, Beurling took the posting.

Beurling next came to the attention of the RCAF and Canada during the

Battle of Malta, when stories began to come out of that embattled isle

about a Canadian fighter pilot called Screwball Beurling who was hotter

than a 10-cent pipe.

Beurling had refused to accept a commission as a pilot officer. Finally

the RAF told him he was an officer whether he liked it or not and moved

his gear to the officers' mess. George, however, continued to eat with

the sergeants. The next day he shot down three 109's.

"In Malta we never used all that code stuff on the air. When we called

a guy up we called him Joe or Pete and they started to call me Screwball

because that was a word I used in describing things. You know, like 'What

a screwball kite this is' and that sort of thing. I got the name Buzz

for something else,'' and Beurling made a low sweeping motion with his

hand simulating a low-flying aircraft buzzing a field.

The RCAF's interest in Beurling increased in the fall of 1942 when word

was received that the great individualist, with a score of 29 enemy aircraft

destroyed, would soon return from Malta for a rest. Beurling had been

wounded in an air battle on Oct. 14.

Target for an Me109

Beurling remembers it all clearly.

"It was one o'clock in the afternoon and I was closing in on a 109G,

riding the prop with about 440 on the clock. I had given him one burst

and was contemplating another shot when I had a hunch that I should break.

I often have hunches and they have saved my life more than once. Just

as I was about to break there was a slapping sound on my Spit and my legs

were buffeted all over the cockpit. The controls jammed, oil filled the

cockpit and I started down in a left-hand power spin. I managed to crawl

to the door and fall out. The chute opened with a big slap and then the

109 who had shot me started target practice on me. The ones that came

close went zip and the tracer that was missing me by quite a bit went

whoosh. One of our guys came along and chased him away and I hit the drink.

My dinghy opened all right and it was then I noticed that I was shot in

the heel.

"The air-sea rescue launch came out with the German bullets spattering

all around it and they drove on as though they were in a regatta. They

took me back and they had to build a new heel on my left foot. I got an

immediate D.S.O. that day," he said.

On that one mission, Beurling had shot down four aircraft, probably destroyed

two more and damaged one, bringing his Malta score to 28, his over-all

total to 29. He and three of his squadron mates had taken on 80-plus Germans.

The Liberator that took him and a score more airmen out of Malta overshot

the Gibraltar runway and crashed in the water. Beurling, his shattered

leg in a cast, but his judgment unimpaired, saw trouble ahead when the

pilot came over the end of the runway on his approach. He hobbled to an

escape hatch and by the time the big plane hit the water he had already

jettisoned the hatch and was ready to dive into the water. He swam 150

yards to safety.

He returned to Canada early in November, 1942, and began a tour which

set several records in hero worship, bond selling and bad taste. In his

native Verdun he received 29 red roses, one for each foeman he had slain.

Each rose was presented by a pretty girl. He went from coast to coast

while thousands cheered, gawked and bought bonds for victory. As the show

hit the road a murmurous clangor filled the star's ears until almost all

of it became completely meaningless.

"If I were ever asked to do that again I'd tell them all to go to

hell or else ask for a commission on the bonds I sold.

The Big Letdown

He found himself falling victim to a combatant's occupational

malaise, a great impatience with the people at home because they didn't

know and couldn't know what it was like over there.

"They say I got swelled-headed but I don't think I did. All I wanted

to do was to get away from those crowds and get back on operations. I

had a lot more combat hours to get in," he says.

In Vancouver he met Diana Gardiner, widow of a fighter pilot, and they

were later married. Their childless marriage recently ended in divorce.

"I guess I'm not a family man. I like flying too much and was away

a lot," said Beurling of his unsuccessful marriage.

Back in Britain, and still in the RAF, Beurling was given a posting to

training command. The brass said to him in effect, "You're the best

deflection shot we've got so you've got to teach others how to do it."

Beurling, who talks about himself and his talent with the same blunt scientific

impersonality as he discusses the shortcomings of others, believed then

as he does now that there is a strict limit to what can be taught. Unless

you've got a calibrated mental gimmick in your skull like George himself

you will probably never be terrific as an air shot.

He stuck the gunnery course from May through to September, 1943, and when

the RAF, which is still his favorite Air Force, still showed no signs

of putting him on operations again Beurling forgave the RCAF for once

spurning him and said he would transfer.

The Ace On the Carpet

The swearing-in ceremony at 20 Lincoln's Inn Fields,

the RCAF headquarters in London, took place while movie cameras ground

and senior officers beamed paternally on a native son come home. But first

it was necessary to get a hat for George. One of the conceits of fighter

pilots was to take the ring stiffener out of their caps so they would

subside into an amorphous "operational" blob. It was even said

that fighter pilots on arrival in heaven took the rings out of their halos.

Beurling's hat looked as though the camel corps had held maneuvers over

it. A hat was borrowed from one of the service photographers and the ceremony

went on and George went into the RCAF.

Right from the start there was an awkwardness about the new alliance,

due in part perhaps to a remark dropped conversationally by the newest

member of the RCAF. Beurling said after the swearing in that he had slept

the night before in the park across from RCAF Headquarters because he

had no place to go.

It was patiently explained that this was no way for an officer to act

and he was sent on his way to an RCAF station, taking with him much wise

counsel and leaving behind him the misgiving that perhaps the highly individualistic

hero might not fit too well into the well-disciplined RCAF machine.

"None of the RCAF wings wanted me. I had a reputation for being hard

to handle said Beurling. But he recalls the part played in his career

by Air Marshall W. A. Curtis, now Chief of the air staff in Ottawa, with

gratitude. [illegible] wise and kindly advice remains as one of the few

bright spots in Beurling's memory of the RCAF.

He Gave Himself Leave

"When I flew with them I flew as tail end Charlie

in red section, a place reserved for sergeant pilots," said Beurling.

"Even there I shot down some Germans and some of them didn't like

that. The officers on the wings seemed to resent me. I probably said a

few things about the way they were operating they didn't like, but I never

did like sloppy operations and I've always said so."

Beurling was given various jobs in connection with gunnery instruction

and says he accepted these noncombatant assignments without a whimper.

However, things did not go smoothly and one RCAF officer reported back

to Lincoln's Inn Fields that Beurling had been seen throwing his hat in

the air and shooting at it with his service revolver. And he was hitting

it, too.

The uneasy mating of George Beurling and the RCAF came to an end in May,

1944, when word came from the station where the fighter pilot was stationed

that he was being court-martialed for low flying. The official version

was that Beurling, in defiance of a new and stern directive, had taken

a Tiger Moth and loudly beaten up the station while all the squadron leaders

and top brass were deep in conference.

Beurling's story is this: "I had been over at another station giving

some gunnery instruction and had taken a Moth to make the six-mile trip.

The ceiling was only 300 feet and I had to fly low. It was a routine flight

under low cloud, that's all." He's still angry about it.

Some of the unhappy aspects, of court-martialing a hero, such as the bad

publicity, were pointed out to his senior officers in the field by calmer

minds in London who were further away from the problem and Beurling and

consequently felt they had a better perspective. The court-martial was

quashed and Beurling who sometimes has the feeling he can't win except

in combat was criticized because he had beaten the rap.

He thought of going to India, but rejected the proposition when he found

out how few Japs there were to fight and returned unwillingly to training

command. He sent in his resignation and without waiting to hear of its

reception took off his tunic, a tunic bearing almost the whole heroic

spectrum of medals - the Distinguished Service Order, the Distinguished

Flying Cross and Distinguished Flying Medal and Bar. All decorations were

received in 1942 while he was stationed at Malta. The DFM is the decoration

for non-commissioned pilots and is regarded by connoisseurs of gongs as

the toughest and best to get. Then he gave himself leave. He was discharged

in Montreal in September.

That was the end of Beurling's short unhappy association with the RCAF.

He would never join it again, he says, under any condition. In the RCAF

itself there is resentment against a man who, some think, thought he was

bigger than the force. There is, too, a deep regret that Beurling's individualism

would not permit him to stay and grow with the RCAF.

Reflecting on this, a senior officer said recently, "He could have

been another Billy Bishop—a distinguished citizen. I wish there

were something we could do for him, but even if he wanted to I don't think

he would fit into the peacetime RCAF where discipline is even stricter

and flying is even more standardized than it was during the war."

They May Even Have Spitfires

Beurling is looking forward to the future with

new interest and enthusiasm. The last eight months have been bad,

he says, but now that his course of action is clear he feels that

he is fulfilling a destiny which was indicated when as a child of

14 he learned to fly. His face brightened as he spoke of possible new theatres. "They may even have Spitfires out there in Palestine," he said and paused. The slightly surging buzz of a distant aircraft came down the soft spring air to the hotel room. "Stinson," he said & then continued. "They came to me and said they were going to buy bombers, but I talked them out of it. Now they're going to buy fighters. It will be a war of shallow penetrations with lots of strafing. The Jews have four former Luftwaffe pilots lined up to fight with them. I've met one of them. He's in Detroit now. His brother was shot down over Malta." Beurling grinned. "No, not by me. We checked that. An Englishman shot him. But he's a keen type, this fellow. Really interested in combat." Beurling stood up and stretched his six feet of well-nourished fighter pilot. He had been sitting for a long time talking. When he talks air war he forgets the time. |

Glad to get back into combat Glad to get back into combat |

We went down to the street. The fine spring day had suddenly turned cool.

"I don't care what you say about me. I don't care what anyone says any more. But don't bring my family into the article. My father's a religious man and he doesn't like wars. One night when I was talking about air combat he looked worried and said 'George, when you look like this I don't know you,'" said Beurling.

We shook hands and said good-by. Beurling turned up the collar of his topcoat and thrust his hands deep in the pockets as he walked down the street all alone.

_________________________________________________

--- Beurling ---

--- Canadian Aces ---

_______________________________________________

On these pages I use Hugh Halliday's extensive research which includes info from numerous sources; newspaper articles via the Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation (CMCC); the Google News Archives; the London Gazette Archives and other sources both published and private.

|

Some content on this site is probably the property of acesofww2.com unless otherwise noted.

![]()